If you’re making a descent and going straight down will generate too much momentum (gravity) to keep your speed at a safe pace, try to zigzag your way across the slow. This will compensate for the degree of the slope since you are going more sideways than vertical. With the wider profile of a turning sled, there will be more natural resistance from the slope. Try to find natural features in the terrain (such as bumps, bushes or old sled tracks) to help you initiate your turns. Keep your speeds manageable and you will be able to safely navigate your way off the mountain.

Although most glove liners are attached to the shell, often you will have these liners become detached. So when you remove your hands (especially if there’s any moisture involved) the liners pull out making it nearly impossible to put your hands back into the finger holes. Your brake lever can work to get the liner back into the fingers of the glove shell. Since it’s rounded, you don’t run the risk of tearing the liner. Just work one finger at a time until the liner is back in position. Also, at the end of the day, don’t leave your gloves wadded up in your gear bag. Take them out, lay them out and let them dry/air out. This will prevent mildew and help them to retain their shape and effectiveness

It’s been said that if your extremities get cold, you get cold. And that’s certainly true when it comes to your hands. Cold hands can make for a long day. However, there are ways to warm up in the coldest temperatures. First, all snowmobiles have exhaust pipes which are radiant heaters. Sometimes you just need to open the side panel and put your hands (still inside your gloves) near the exhaust muffler. Keep in mind that sometimes the muffler can be hot enough to melt fabric so you want to maintain some distance or minimize the direct contact. Next, the exhaust muffler also offers forced air. Just tip your sled on the side and allow the exhaust to warm your gloves/hands. Finally, turbo sleds usually have a air vent to remove under-hood heat. This radiant heat will also serve as a great source to warm hands.

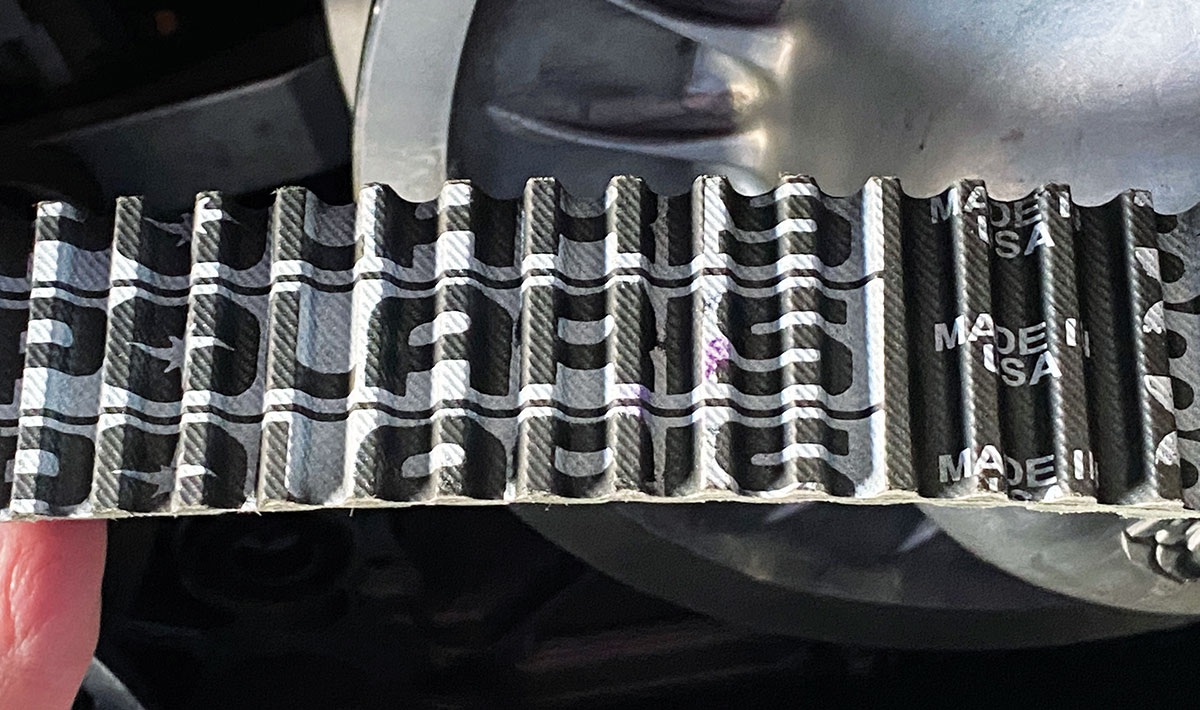

There is a right and wrong rotation direction to your drive belt. The right rotation will have the proper orientation of the belt lettering (you can read the brand) when installed on the sled. If the lettering is upside down, your belt rotation will be opposite of its intended design.

Although spark plug fouling has become less common with better fuel delivery systems, a loose cap or bad connection could create problems. Make certain your cap is always securely connected.

You can use dielectric grease to prevent corrosion while maintaining conductivity. Also, you may choose an aftermarket waterproof rubber cover resister cap which usually will secure better than an OEM spark plug cap.

The cost is less than $5 per cap and the installation is easy.

Don’t look out for that tree. We all know the familiar jingle of the 1967 cartoon or 1997 movie where a spoof on a Tarzan character would swing from a vine and smack into a tree.

Well, sometimes as snowmobilers we tend to claim “a tree just jumped right out in front of our sled” while we were minding our own business. The truth is, snowmobiles tend to go where the eyes are fixated.

If you’re staring at a tree, you’re likely to steer into the tree. The key is to not “look out for that tree,” but to look to the gap between the trees.

Look to where you want to go, not to where you don’t want to go. This helps you commit to a line and trust your snowmobile to do what you want it to do.

Often we find ourselves working our way off a mountain down through trees. The problem is that sometimes the trees get too thick or there’s too much downfall and you end up in some terrible messes. Try to stay on a descending ridgeline or spur as long as possible. This allows you to usually get farther down the mountain while maintaining more options on what direction you can go. However, usually at the lower point of the spur, the terrain is prime to have a creek bottom. Usually the spur drops straight off into the creek. Just before this point you should be able to pick what side of the spur offers the best opportunity to complete your descent and best options to crossing the creek.

The trick to getting good photos is to find good light. Although you can get good shots in the shade, you will always get better photos in the light. Although you don’t always need direct sunlight, there will always be better contrast in direct sun. So if you are in the trees, look for areas of sunlight to capture your photos. If it is a partly overcast day, wait for openings in the clouds to shoot your photos. Basically, look for your openings where the sun is shining and set up your shots so you can capture your object when it hits the opening.

Since the modern sleds have an easy push-button reverse, I will sometimes use this technology to help me dig into a side of a mountain to slow my descent. Basically what I do is the moment I realize that my brake isn’t going to slow me down, I lock my track (which stops my clutch from spinning) and then I push the reverse button. Before I release my brake, I engage the throttle to initiate the reverse direction of the clutches and then I slowly release the brake as the throttle takes control of the track in the reverse direction. (You don’t want to slam the clutches turning one direction into the reverse direction … you could end up with a lot greater problems while still encountering an uncontrollable descent.) Once my track starts trying to dig down, the sled usually comes to a complete stop … which allow you to control your speed and repeat the process.

We sometimes fail to take in to account is that when you’re coming down on a 500-pound chunk of metal on various forms of frozen ice, the power of gravity takes over. Steep slopes (or objects that are on them) are the No. 1 one cause of snowmobile damage. Ironically, on some descents, the only control over your snowmobile is with the throttle, not the brake. When a track is locked (not rotating … a condition caused when you have a fistful of brake), the lugs in the pattern fill with snow. Once the pattern is full, you’re basically sliding on snow with no traction. Also, if the track isn’t turning, you have no control of the sled … gravity is in charge. If the track is turning, it still maintains the ability to push the sled in the direction it’s pointing. Now if you’re going down hill, you may be able to get the front to point from one side to the other. Then, by grabbing the throttle, you can at least alter your downward direction by going at an angle. (This can come in handy when you have to hit a gap in the trees somewhere along the descent.) But this does require quite a bit of conversation between the brain, the thumb and the eyes.

Brain: “What are you doing? You are already going too fast.”

Thumb: “But I have to power to the left to hit that gap in the trees.”

Brain: “But if you don’t hit that gap, you’re definitely going to hit something.”

Eyes: “That gap ain’t that big. And those trees are.”

Brain: “Shouldn’t we be grabbing for that left-hand lever thing?”

Thumb: Trust me on this one. Speed is a good thing right now.”

Eyes: “I can’t take this anymore. I’m closing.”

Brain: “Hey, everything went dark. Are we dead?”

Butt: “I don’t know about you guys, but I just sucked up a seat.”

The first thing you should understand is that the decisions you make on the top of the descent will have the greatest impact at the point of descent where speed and gravity take over. So here are a few things to know. First, knowledge of where you want/need to end up is useful. If there’s a run-out, it’s just a matter of picking the line to your run-out. If not, you need to know how you’re going to slow your sled down before the bottom.

For mountain riders there are two certainties—we go up and we come down. Going up is usually the easiest. You point and grab throttle. You usually have the ability to pull out of a climb at any time. But coming down in steep terrain there are times when gravity works far better than the brakes of your snowmobile. Controlling you descent can be a challenge. Sometimes, rather than going straight down a mountain slope, you may want to lean into the sidehill and take your descent at an angle that allow you to control you speed and study the terrain below before you make that final commitment.

Hardcore snowmobilers have two things in common: first, they want to ride as light as possible; and second, they way to make certain they are prepared for what can happen on the trail. That’s why some will have an extra brake lever stashed on their sled. When riding trees, the probability of breaking a brake lever increases … and from personal experience, riding off a mountain without a brake is not fun. Some snowmobile manufacturers are actually designing a brake lever with a notch at the midway point which gives a “breaking point” for the brake that still allows enough lever to safely navigate your sled back to the trailhead. If your brake lever doesn’t have this, you may consider picking up an extra lever … just in case.

Always take a minimum of two pairs of gloves for a ride. The least you want to have is a thicker, warmer pair for on the trail early/late in the day when temperatures are at the coldest, and a thinner pair during the day when you are more active. Taking three or four pairs make the most amount of sense if you have space for them. And it doesn’t hurt to have an extra set of goggles as well.

Sometimes the terrain can be steep and it’s hard to zigzag or find enough snow to slow your descent. In these conditions I look for bushes or small trees to hit to offer more resistance to gravity. Naturally, you don’t want to smack hard into a big tree. I look for little ones that will either fold over while slowing me down. Or I will try to slide sideways into the tree and take the impact with my track and rear suspension. But what I’m trying to accomplish is to use a tree or small bushes to stop me on the hill so I can recalculate my descent and reestablish my line while calculating my next natural stopping point.